Tiffany was the best colorer in our first grade class. She would draw along the outline of the image with a dark, steady and confident stroke of her crayon. Then, gently and evenly, she would complete the inside with just the right colors. (Except for skin. For some reason, she always thought yellow was the best color for people’s skin.)

I would try to copy Tiffany’s technique, but my dark outline looked somehow ominous and less confident. As if the crayons themselves were aware of that border’s lack of authority, straggles of color always escaped from within the lines.

“You’re good at art,” I remember telling her. Growing up, seeing my abilities, compared with what some other kids were able to do, I formed a concept of myself as “not artistically inclined.”

“But you’re so creative!” was the encouragement I’d hear from people who knew the wild stories I wrote and the other projects I concocted. “I know,” my answer would be. I allowed the label of creative. “But I can’t draw.”

Well, something has happened to me this year. More likely, it’s been happening since becoming a parent ten years ago, which has caused me to look and to see in new and different ways every day.

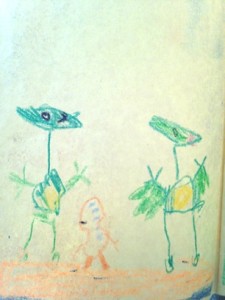

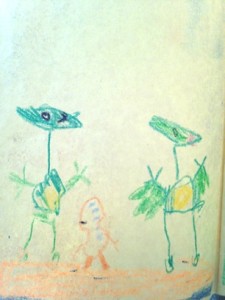

When my older daughter was three or four, she loved the PBS show Dinosaur Train. One day, she made some drawings that depicted a series of scenes from that show. Looking at her picture of the dinosaurs, I noticed that she drew blue stripes along Buddy the T. Rex’s head and back. “Buddy has blue stripes?” I thought… and in watching the show again, sure enough, he did.

When my older daughter was three or four, she loved the PBS show Dinosaur Train. One day, she made some drawings that depicted a series of scenes from that show. Looking at her picture of the dinosaurs, I noticed that she drew blue stripes along Buddy the T. Rex’s head and back. “Buddy has blue stripes?” I thought… and in watching the show again, sure enough, he did.

On the next drawing, she showed the train from above, heading off-screen. I would have drawn the train in predictable shapes and in full view, and not from above… I would have drawn the train as I interpreted it through my lens of expectations and experience, rather than how it was actually presented on the screen.

On the next drawing, she showed the train from above, heading off-screen. I would have drawn the train in predictable shapes and in full view, and not from above… I would have drawn the train as I interpreted it through my lens of expectations and experience, rather than how it was actually presented on the screen.

I realized that she and I look and see differently. And when she started doing paintings that looked to me pretty amazing for a young child, I suspected it was because of the way she looks at things. (And, note to Tiffany, she uses three or four different crayons to create a particular skin tone :)).

Here are her sunflower, painted when she was four, and fire, painted when she was five.

Fast-forward, to last year, when I started to get this urge to draw my beautiful dog, Casey. I joke that her cuteness is beyond comprehension, so I think I wanted to draw her to try to understand what I was feeling. Well, I was taken aback when what I drew somewhat resembled what I was trying to draw. I mean, it wasn’t a masterpiece, but for me, it was like nothing I’d been able to do before.

I thought that this result was just a fluke, and that I could draw Casey because I love her so much. I thought maybe the emotions around what I was doing gave me access to a higher power, where genius resides, and I was able to let a little of that through. And I still think that may be part of the shift that happened. But over time I felt compelled to draw other dogs, especially when I saw lines and wrinkles.

Then, I started doodling on my daughters’ napkins on their school lunches. I just love the critters that illustrators Jan Brett and Jane Chapman bring to life in the picture books I’ve read to the girls thousands of times. So, I riffed off of those animals, and was surprised to find that I could reasonably re-create some of those furry characters with pen on a napkin.

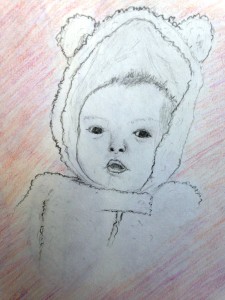

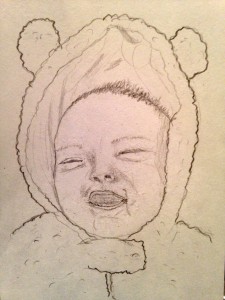

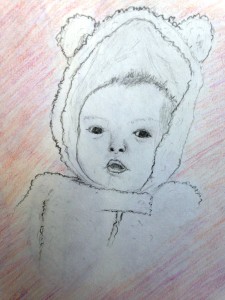

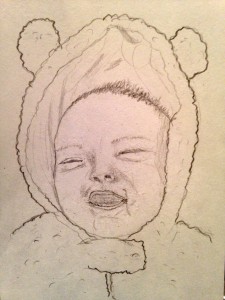

Last month, a dear friend had a baby girl, and sent me some

Last month, a dear friend had a baby girl, and sent me some

pictures. And, you guessed it, I was so inspired by the sweetness and newness of this tiny person, that I needed to try to draw her.

At this point, it occurs to me that something is really happening here. But what? I can’t draw. I can only draw Casey. OK, I can only draw Casey, and some other dogs who are floppy and wrinkly. And also maybe critters on napkins. And babies.

I think what is happening is that I am looking at things differently. As I tried to draw that sweet little face, I kept wondering things like, “Why doesn’t this side of her face look right?” and then, at some point, a shadow would emerge that I hadn’t noticed before and I would lightly shade that part of the drawing, and it would make all the difference. I would stare and stare and suddenly realize, her eyes are not actually on the same plane. The left one is lower, in line with that wrinkle on her hood…

So this process of drawing seems to be as much an allowing of the picture to express itself to us, as it an attempt to manipulate the pencil and eraser.

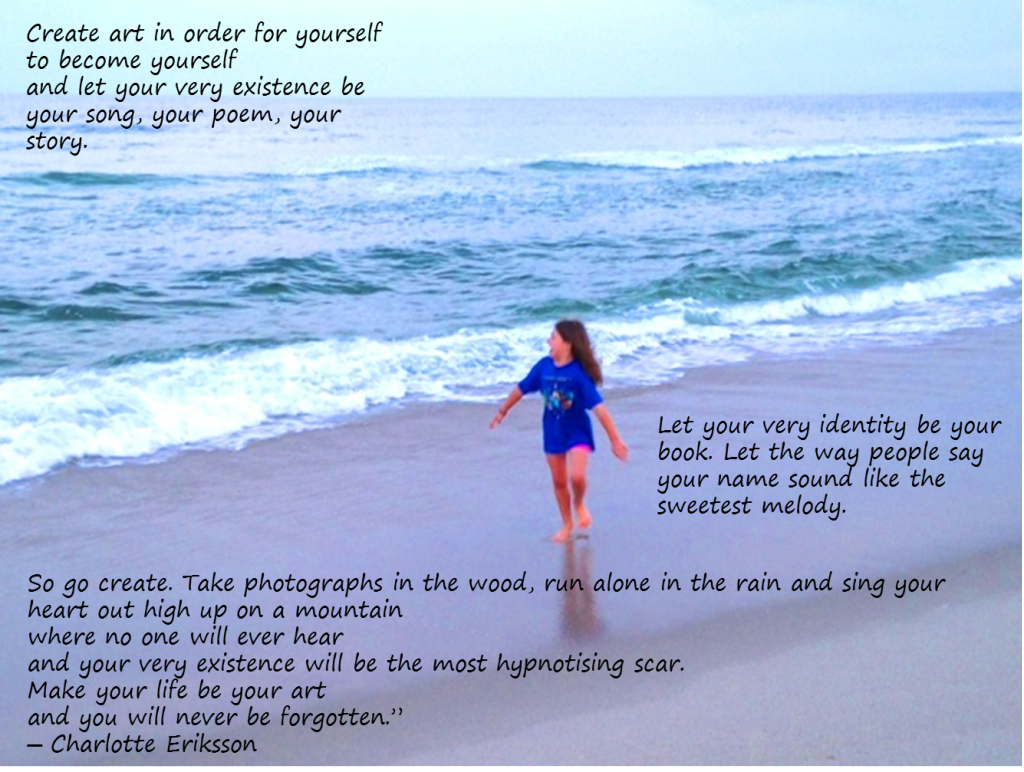

I think the other thing that is happening is that I am looking at myself differently as well. The idea that I am a person who “can’t draw” comes from my former, fixed mindset. Throughout my research in psychology and education, both in my career and in my personal journey, I’ve come to believe in the potential we all have for growth and change. It seems that I have developed a “growth mindset” (check out the book Mindset by Carol Dweck). The growth mindset views genius as made and not born, and sees failure and challenge as foods that nourish your genius.

Dr. Dweck says that a growth mindset can be taught and developed. So if you feel you may have a fixed mindset, whenever you hear your fixed mindset say “I can’t…” answer it with a growth mindset. Add the word “yet.” Allow yourself to see your struggles as vital components of success.

Betty Edwards, author of Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, says “It seems that your brain already knows how to draw. You just don’t realize it. Helping people move past the blocks to drawing is, however, the difficult part. The brain, it seems, doesn’t easily give up its accustomed way of seeing things.”

How do you see? Are you open to the idea that things are not always as we expect them to be… and that you may have new talents, waiting to be developed?

I am still learning. I don’t really know how to see myself now, or whether to believe that I am actually learning this “ability.” But I know how I see failure. There is no such thing, as long as you are growing. The only real failure is not trying at all.

I have some sad news to share. Last month Casey, my muse, my mascot, my writing partner and four-legged best friend for 13 years, left the physical plane. She had a massive seizure, most likely a complication from a tumor that was close to her brain.

I have some sad news to share. Last month Casey, my muse, my mascot, my writing partner and four-legged best friend for 13 years, left the physical plane. She had a massive seizure, most likely a complication from a tumor that was close to her brain.

Floating in the air we saw white fuzzy dog-fur-looking dandelion seeds. And the next day, a doe moved into our back yard and helped herself to a buffet of weeds!

Floating in the air we saw white fuzzy dog-fur-looking dandelion seeds. And the next day, a doe moved into our back yard and helped herself to a buffet of weeds!

When my older daughter was three or four, she loved the PBS show Dinosaur Train. One day, she made some drawings that depicted a series of scenes from that show. Looking at her picture of the dinosaurs, I noticed that she drew blue stripes along Buddy the T. Rex’s head and back. “Buddy has blue stripes?” I thought… and in watching the show again, sure enough, he did.

When my older daughter was three or four, she loved the PBS show Dinosaur Train. One day, she made some drawings that depicted a series of scenes from that show. Looking at her picture of the dinosaurs, I noticed that she drew blue stripes along Buddy the T. Rex’s head and back. “Buddy has blue stripes?” I thought… and in watching the show again, sure enough, he did. On the next drawing, she showed the train from above, heading off-screen. I would have drawn the train in predictable shapes and in full view, and not from above… I would have drawn the train as I interpreted it through my lens of expectations and experience, rather than how it was actually presented on the screen.

On the next drawing, she showed the train from above, heading off-screen. I would have drawn the train in predictable shapes and in full view, and not from above… I would have drawn the train as I interpreted it through my lens of expectations and experience, rather than how it was actually presented on the screen.

Last month, a dear friend had a baby girl, and sent me some

Last month, a dear friend had a baby girl, and sent me some